Reinventing Grandparenting: I never became a mother, but I’m a grandmother now

When many of my women friends were either getting pregnant or longing to get pregnant, I used to think that I was missing a chip. I watched and waited for a maternal feeling, desire, or impulse of any kind – to no avail. As far as I was aware, during those years, I wanted only one thing: to become enlightened.

At 19, I was hooked on meditation and its promise. And when I saw the suffering all around me, near and far, I wanted only to be free of it.

My mother was devastated by this turn of events. She had flirted with early feminism and assumed that, unlike her, I would have both a career and kids. But neither called to me like the devotion to my spiritual vision.

Fast forward two decades, past midnight on my biological clock: I met a man whose spiritual devotion was as fervent as my own – and he had kids. Another two decades later, they have kids – and I’m Grandma Connie.

Given that I had no experience as a parent and no positive grandparent to serve as an Elder for me, I’m reinventing it as I go, developing as a grandma while the kids develop as toddlers. And because I know that many of our early unconscious negative images of age stem from our grandparents, I feel acutely aware of my impact on them.

Today, when there are more Americans over 50 than under 18, many Boomers don’t share this privilege of deep contact with grandkids. Our culture has shifted from multi-generational homes to rampant age segregation, with young people in school for long hours, middle-aged people at work for long hours, and older people in retirement communities or nursing homes. Age segregation is as widespread as racial segregation.

The result: Vast numbers of youth will grow old without close relationships to older people and will default to stereotypes. (Beware: the inner ageist!) And older people miss the vitality of relationships with youth and the opportunities to serve their families.

Despite this geographical or residential separation, we need to acknowledge the elder wisdom that we want to transmit and pass it on. Great-grandfather Jerome Kerner, 84 and co-chair of Sage-ing International, speaks and writes about grandparenting. He told me that, because his mother worked, his Nana was his primary caretaker, and her unconditional love provided him with emotional regulation. Without grandparents, Jerome told me, kids turn to social media, video games, or drugs to find this regulation and to offset the pressure of parental authority, school performance, and competitive sports.

Pat Hoertdoerfer, a grandmother of seven and a retired Unitarian Universalist minister, who is also a Sage-ing leader, described for me a unique family tradition to transmit values and a sense of belonging. In 2009, her family launched Cousins Camp to nurture the grandparent-grandchild relationship for a week each summer. “During Cousins Camp, we strive to live our core values, transmit family heritage, engage their imaginations, learn from each other, live close to the land, and play together. We enjoy waterfront activities, games, arts, and story time. Responsibilities are shared, privileges are shared, conflicts are resolved in Camp Council, and love is celebrated.”

They begin the week, Pat told me, by defining their Cousin Camp Promises: To act with kind words, helping hands, caring hearts, open minds, listening ears, and walking feet. They discuss these six promises and agree to practice them each day.

In council, they share how they could all do better. And they end council with an affirmation for each cousin: “You are a person, you are special, you are important. Not because of what you look like, not because of what you have, not because of what you can do. Just because you are You.” (In my language, this means shifting the relating from ego to soul.)

I was deeply moved by Pat’s story. But I realize that most families cannot meet this ideal. For some, there are conflicting values and distrust between generations. One client, a grandmother, told me that she deeply dislikes the materialistic, consumer-oriented values of her grandson’s parents. She believes they supply him with stuff instead of supplying him with emotional support.

A grandfather told me that his adult children don’t make time for imaginary play with his grandkids; they are so focused on perfectionistic performance that the young ones already show signs of anxiety.

And another grandmother told me that her grandkids are parked in front of their Ipads or TV for hours each day. She cried as she described her powerlessness in this heartbreaking situation.

I share her concern. Research reported in Virtual Child by Chris Rowan confirms that the youth epidemics of attention disorders, aggressive behavior, lack of empathy, learning disorders, and obesity are correlated with overuse of technology. Some include autism in this list. Kids are using virtual avatars to replace parents and friends. In some cases, their content is loud, violent, and sexual, which kids imitate on the schoolyard. Some 75% of kids have tech in their bedrooms. They develop videogame brain, which hardwires them for a lack of impulse control.

The long-term result: They are isolated from family members, lonely, failing to read books, depressed, getting medicated, eventually truant from school, and at risk for obesity and diabetes. The combination of being sedentary and overstimulated is perilous. The loss of normal brain development and human interaction has dire consequences.

Yet most parents are not setting limits on tech. They are constantly checking their own devices, and allowing kids to bring them to dinner, on vacation, in the car, and to bed.

The antidote: Twenty minutes of access to natural green space reduces risks of ADHD. Twenty minutes of cardio exercise increases attention span. Physical touch calms the nervous system and reduces arousal. Deep listening enables emotional regulation and empathy.

These findings provide guidelines for conscious grandparenting. As Jerome Kerner pointed out, we can offer these antidotes. We can share the joys of play in the natural world and the rewards of exercise and exploring new things. We can talk about the fantasy of games vs. the reality of life. We can teach them how to tune into their own bodies, their feelings, their self-expression, so that, even as digital natives, they don’t lose touch with themselves. Finally, as their parents supervise their ego development, we grandparents can see into their souls.

Are we obligated to support the parents’ values? Or are we obligated to speak our differences?

And how do we grandparent the kids’ shadows, that is, the unconscious material that is inevitably formed by adults’ communication styles or by their making certain feelings, such as anger, or behaviors, such as crying, unacceptable?

One grandmother, a psychologist, told me that she observed how fear was transmitted from her adult son, the parent, to her grandson. Then she watched her grandson develop an anxiety disorder. “But each weekend,” she told me, “I made sure that little boy felt safe with me. He could feel the steadiness of my body and the calm of my mind. And he felt loved no matter what.”

Clearly, each family has its own dynamic: Some will allow for open dialogue among generations, while others won’t. Some will allow kids to express anger, fear, or sadness, while others won’t. Some will allow for no-tech time, while others won’t. But, if we remember that we can be an antidote, we may find a way.

It also became clear to me through interviews that grandparenting can be a spiritual practice for Elders. While parents are absent or distracted, we can practice presence with our little ones. While parents are building ego identities and feeling concern about image, they may be critical of kids who don’t meet their standards; we can practice acceptance and forgiveness. While parents are focused on performance, we can practice spontaneous play or read them stories about heroes and heroines who find their unique gifts. All of these experiences support the development of both Elders and youth.

Finally, I have found some indirect ways to share my values with grandkids that don’t challenge their parents. For instance, my grandson Jayden, 7, and I play the question game when we’re together. “Why does grass grow?” “Where do shoes come from?”

One day, he asked, “Where does water come from/”

As I began to describe how the rain falls on the mountaintops, freezes into snow, melts into rivers, and goes through pipes so that we can drink it, I watched his eyes light up. Something special was happening with this question and answer. I explored further how our bodies are made of water and how everything is interconnected, one living system, like a giant body. The excitement in his own little body was palpable as he sensed a great truth, even for a moment. Clearly, this was not an intellectual understanding but a feeling of opening to all living things. He could feel less separate, less isolated, as he imagined water flowing through him and through his Mom and Dad as it flows from the sky into the rivers and back into him with each glass.

I felt such gratitude that, although I was never a mother, today I am a grandmother.

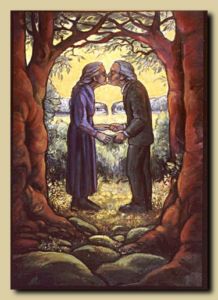

Dr. Connie Zweig recently retired from a long career as a therapist specializing in shadow-work and spirituality. She is co-author of Meeting the Shadow and Romancing the Shadow, author of Meeting the Shadow of Spirituality and A Moth to the Flame: The Life Story of Rumi (a novel). She is currently writing The Reinvention of Age. She is a grandma, a Certified Sage-ing Leader, and a Climate Reality Leader. She is blogging excerpts of her next book on https://medium.com/@

Join over 4,000 Members Enjoying Sage-ing International

Subscribe Here